Colonel Richard Kenney passed peacefully in his sleep, on the morning of Dec. 11, 2014, at his home in Coronado. He was 94. Donations in lieu of flowers were suggested in his memory to the Coronado Yacht Club Junior Sailing Program. “That’s where I started, and that’s where I’d like it all to finish.” he said.

Colonel Richard Kenney passed peacefully in his sleep, on the morning of Dec. 11, 2014, at his home in Coronado. He was 94. Donations in lieu of flowers were suggested in his memory to the Coronado Yacht Club Junior Sailing Program. “That’s where I started, and that’s where I’d like it all to finish.” he said.

Richard F. Kenney, (Dick) was born March 2, 1920, in Santa Cruz, California, one of five children born to Lt. Patrick John and Doris Kenney. His family received orders to Coronado when Dick was three years old. “I went through the whole (Coronado) school system,” Kenney recalled. His father died when he was a teenager. His mother bought real estate in Coronado and stayed to raise her family.

Dick gained a reputation for being a big, athletic kid who liked to work and play with equal passion. Growing up in Coronado, the island, Bay and ocean were Dick’s playground. He would hang out with several boys, who between work and school, would invent mischief. They purchased fireworks and blasting caps from the Coronado Drug Store, being more powerful versions then what is sold now, they could, when placed on the tracks, derail an unsuspecting trolley as it meandered up Orange Avenue.

Dick gained a reputation for being a big, athletic kid who liked to work and play with equal passion. Growing up in Coronado, the island, Bay and ocean were Dick’s playground. He would hang out with several boys, who between work and school, would invent mischief. They purchased fireworks and blasting caps from the Coronado Drug Store, being more powerful versions then what is sold now, they could, when placed on the tracks, derail an unsuspecting trolley as it meandered up Orange Avenue.

Years before he had ever dropped into a cockpit, Kenney exhibited a need for speed. At 13 he was issued a driver’s license so he could cover his North Island paper route. Within a year, he was driving a truck loaded with prize polo ponies onto the Ferry and to pastures in south Bay. He was a teenage entrepreneur and self-employed as a pony tender at the Coronado Polo grounds. He once built a wall (still standing at Third Street and J Avenue) in exchange for an old Buick, and he would do odd chores for elderly residents of the island. While washing the very proper Mrs. Scripps 20-foot long Lincoln Phaeton he would dry it by driving at top speed up and down the Silver Strand, unbeknownst to Mrs. Scripps, of course.

Dick excelled as a junior sailor throughout the late 1930s, winning numerous regattas at the Coronado Yacht Club in Star boats, scows, and the Sunbirds of the Rainbow Fleet. A graduate of the Coronado High School class of 1938, he was, at 94, the last surviving member. He attended San Diego State University in 1940-41, University of Nevada in 1968 and Sierra College in 1972.

Kenney obtained his pilot’s license in 1940 from the Clyde Corley Flying School at Lindbergh Field. In September 1941, after a brief stint on four-stacker destroyers, he joined the Army Aviation Cadets at Cal Aero in Chino, California. Upon completion of Flight school in 1942, he was commissioned an Army Air Corps second lieutenant and assigned to a squadron at Hamilton Field just north of San Francisco. On short notice that Fall, the squadron boarded the Queen Mary in New York sailing for Ireland and the war. On October 2nd as land drew near, Dick got his first taste of the war. During evasive maneuvers to avoid Nazi U-Boat attacks, the converted cruise liner hit military escort cruiser HMS Curacoa, slicing it in half and killing more than 300 men. “We watched helplessly as wreckage floated past our portholes,” he would recall years later. The reality of war had hit home rapidly for the young pilot eager to fight for his country. He soon got to do

exactly that, Flying with the 95th Fighter Squadron in Ireland and eventually deployed to fight air battles in the North Africa Campaign.

At 6’3″ and 190 pounds, Lt. Kenney was a lanky twenty-three year old as he jammed himself into the tiny cockpit of the P-38 Lightning, one of the most significant aircrafts of World War II, and a veritable killing machine. The P-38 Lightning was nicknamed “The Forked Tailed Devil” by the Germans. It had a number of roles in both the Pacific and Atlantic Theaters – dive bombing, skip bombing, ground attack, aerial combat, night fighting and photo reconnaissance. Drop tanks under the wings gave them incredible range, and they could go toe-to-toe with anything the Germans or Japanese could put in the air. It carried a 20 mm cannon, four rocket launchers, and four M2 Browning machine guns, in addition to a respectable load of bombs.

On April 28, 1943, Kenney piloted his P-38 in low (15 feet) over the waters of the Mediterranean and fast (200 mph) to make a direct hit on an enemy merchant, troop transfer ship. Maneuvering himself directly over the ship when dropping his load, the explosion, and resulting shock wave flipped his P-38 past vertical. Disregarding his own safety, he kept his eyes on the ship long enough to watch his wingman’s bomb also explode on the doomed ship’s deck. Suddenly, the radio squawked as one of our bombers flying overhead warned Kenney of Messerschmitts dropping in on him. Kenney righted his aircraft in time for a head-on run with one of the Messerschmitts, guns blazing. Kenney won that duel as the Messerschmitt flamed and crashed into the sea.

Kenney’s bombing of the Axis merchant ship and downing of the Messerschmitt ME 109 that day resulted in his receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. An official description of his actions read like a Clark Gable movie script: “Undaunted by a solid wall of flak and machine gun fire thrown above the ship, [Kenney] attacked broadside, planted his bomb squarely amidships, and passed a few feet over the ship. The merchant vessel was left at a complete standstill belching black smoke and steam after the explosion.”

On another mission Kenney attacked a flight of six Italian transport aircraft (SM-82). He took out the rear transport, and then the next. As he took a bead on the third transport, a Messerschmitt assigned to cover the transports dropped out of the ceiling and opened fire on Kenney’s P-38. Kenney wheeled his plane around and shot down his attacker. That, including the two SM-82s, gave him a total of four confirmed kills. It was a big day as pilots go.

Later, while escorting a flight of B-25 bombers over Sardinia, Kenney and his wingman were under attack by several Messerschmitts. Kenney’s wingman took down one of the German planes, amidst a mixed portrait of planes and hot lead. Kenney’s guns jammed and his wingman had to switch gas tanks so they decided to hit the deck for home at about 400 miles an hour. The Messerschmitts had altitude in their favor, however, and weren’t ready to give up the fight.

“They were dropping down on us fast, and their bullets were exploding at maximum range just outside my canopy,” recalled Kenney. “We couldn’t outrun them so I signaled my wingman to turn back into them. He shot at one and missed, shot at another and it went down. The second plane ran for it and I had the third one in my sights but I was toothless.” Kenney’s jammed guns prevented him from scoring a fifth kill that would have given him ace status, however, and despite having no firepower of his own, Kenney saved his wingman by boldly bluffing the third enemy plane out of the air.

That action resulted in a United Press International story that hit newspapers back home. The headline read, “Coronado Flier Bluffs Enemy.” Richard Kenney complained about that fifth elusive kill until his dying day. Two months after bluffing the German pilot out of the sky, Kenney was sent on a mission to fly in low and strafe a radar tower in Sicily. As acting operations officer, he intentionally put himself in the final slot. “There was never any other option,” he recalled years later. “There was no way I was going to put someone else in that position.” That decision took Dick Kenney out of the war for the duration. His left engine was hit by surface-to-air gunfire, engulfing the plane and him in fire. Unable to reach the Mediterranean , Kenney crashed on a Sicilian farm and, in spite suffering severe burns over much of his body, he made sure there was nothing left for the Nazi’s to get from the wreckage by throwing his “Mae West,”

charts and maps into the flames.

He was captured by the Italians, taken to a hospital in Palermo, handed over to the Nazis and immediately transferred to Germany. Over 17 days of “interrogation,” he had a gun put to his temple, was refused medical treatment, thrown into solitary confinement and nearly starved before being transferred to Stalag Luft III, a POW camp for captured aviators. Located 90 miles southeast of Berlin in what is now Poland, he was to call Stalag Luft III home for the next two years. Kenney’s POW tag read “Stalag Luft III-1747”. He was a “guest” of Adolf Hitler for the duration of the war.

Stalag Luft III was the inspiration for the movie “The Great Escape,” throwing a light on Kenney’s misfortune that gave it (and him) celebrity status in the years to come. While he was not on the list of escaping prisoners, he worked to help make that escape possible, often times carrying dirt from the tunnels in his pant legs to be spread outside when the Germans weren’t looking; or standing night watch as the diggers burrowed underground towards their intended escape. Kenney later said of the movie, “The main characters are combinations of several people. The movie is mostly very accurate. All the events really happened, except for the motorcycle scene with Steve McQueen.”

In January of 1945, as Russian troops closed in on Stalag Luft III, Hitler ordered all 11,000 POWs be moved to prevent their capture. He intended to use them as gambits, as his war crumbled around him. The POW’s were marched out at midnight in a blinding blizzard. The now infamous death march was 60 miles, through the worst snowstorm to hit Europe in fifty years. Dick Kenney was one of those men who marched, starving through snow and ice, in sub-zero weather. “We thought the Nazis wanted to use us as human shields and hostages. We were given 30 minutes to grab some of our belongings and get ready for the march,” remembered Colonel Kenney. “The date was January 28, 1945. I’ll never forget that. My bunkie [bunk mate] and I were near the end of the column. It was bitter cold, and we lived off discarded food that had become too much of a burden for the emaciated Kriegies [POWs] ahead of us to carry, despite the German guards’ threats that they

would shoot anyone picking up discarded food.”

For six days the prisoners slogged through the worst possible winter conditions. Finally the Germans packed the POW’s into small boxcars up to 70 men were forced into the filthy cattle cars that would have been crowded at half that number, “That was the worst,” said Colonel Kenney. “Those boxcars were cold and they didn’t even have a pee hole. There was no room to lie down, and the smell was like nothing we had ever experienced. There were cattle droppings on the floor and we couldn’t see out.” A modest description at best, in truth, the floor was also covered by three days of vomit and excrement. The only ventilation in the cars came from two small windows near the ceiling, at opposite ends of the boxcars. Meanwhile, the train continued on through the frozen countryside and bombed out German cities and on to an impossibly overcrowded Stalag Luft VII and months of starvation.

“On the morning of April 29, 1945, elements of the 14th Armored Division of Patton’s 3rd Army attacked the SS troops guarding Stalag Luft VII. Prisoners scrambled for safety. Some hugged the ground or crawled into open concrete incinerators. Bullets flew seemingly haphazardly. Finally, the American task force broke through, and the first tank entered, taking the barbed wire fence with it. The prisoners went wild. They climbed on the tanks in such numbers as to almost smother them. Pandemonium reigned. They were free!”

Red Cross resources had been re-appropriated or looted by the Nazis. The liberating US troops could not feed the more than 130,000 starving men. Dick Kenney was starving and just wanted to go home. He slipped out of the camp with an Army artillery unit and made his own way across Europe arriving at Camp Lucky Strike in France with no dog tags or uniform, but one step closer to home.

After returning to the U.S., Kenney was undergoing a refresher flight-training course when he was offered the opportunity to become an instructor pilot for aviators flying P-51s. Along the way he met and flew with Colonel Robert L. Scott, the author of “God is My Co-Pilot.” Since Kenney flew with Scott on several occasions, Kenney presumably was at least a minor deity among his peers and younger aviators.

Colonel Kenney trained combat crews in aerial gunnery, bombing and strafing at Nellis Air Force Base in mid-1953. In search of that elusive fifth kill to qualify him as an ace, Kenney signed up to fly in the Korean War, as the squadron commander of a Saber jet outfit. The war however was all but ended, and he missed his chance to achieve the title of “flying ace.”

In Korea, he flew as the squadron commander of a Saber jet outfit, crucial in instructing Navy fliers in the transition from prop to jet propulsion, becoming one of the first Air Force flyers to get carrier qualified. Later, Dick was sent south of the border as an emissary of the United States Air Force, to aide the Mexican Air Force’s transition from propellers to jets. To add to his unique collection of awards and honors, he was presented a set of third-world “wings” from the Mexican Air Force as an honorary member of that allied force.

Following the Korean War Kenney was assigned to the Pentagon and flew F-86s with the DC National Guard at Andrews Field, Maryland. Upon completion of this tour he was assigned to fly F-100s out of Foster Air Force Base in Victoria County, Texas until the base was closed in 1958. “I loved that assignment,” recalled Kenney. “I worked for my former commanding officer in Korea and at Nellis, and the base was in the heart of some of the greatest hunting and fishing in Texas. As commander of a squadron it was good duty.”

Stationed at Misawa, in a remote portion of Japan, his squadron stood nuclear alert in Northern Japan. Lt. Col. Kenney transitioned the squadron from obsolete, straight winged F-84s to the Super Sabre F-100s.

Kenney returned for his second tour at the Pentagon and to flying F-100s with the DC National Guard. He was then assigned as advisor to the Sioux City National Guard and promoted to full Colonel. His final military assignment was at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina as deputy commander of operations for the 354th TAC Fighter Wing flying the familiar F-100 with a NATO commitment.

Dick flew for the Army Air Corps/US Air Force for 27 years, logging 6,000 flight hours that covered two wars. “Flying was my life,” he often said proudly.

Additional duty stations and positions after the War included commander, Tactical Training Squadron – Nellis AFB (F-86); commander 721st Fighter Day Squadron, Tactical Air Command, F-100; commander 451st Fighter Squadron, Tactical Air Command, F-100; commander 416 Tactical Fighter Squadron, F-84/100 – Japan. Colonel Kenney retired in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina as Department Commander of Operations for the 354th Tactical Fighter Wing.

After retiring from the military Kenney co-owned the Nordic Ski Center in Squaw Valley, California. He was a member of the North Tahoe Search and Rescue Team, president of the Lake Tahoe Ski Club, an official for the United States Ski Association, as well as a Technical Delegate of the International Skiing Federation (ISF).

Kenney was active in the ski industry until 1983 when he moved back home to Coronado where he lived out the remainder of his life. The ISF and the United States Ski Association honored Kenney in 1985 for his work and unparalleled contributions to the sport.

Colonel Richard Kenney enjoyed his final years in Coronado, riding his bicycle and working on his 36-foot Grand Banks trawler from which he fished and escaped the July Fourth crowds on Coronado.

The media loved Dick Kenney. After World War II he seemed to be forgotten. But, in his 90s, he was featured in the San Diego Union-Tribune twice, on two TV news stations, the subject of two KPBS specials, and featured in articles of local newspapers numerous times. In his interview with KPBS reporter Ken Kramer, Kenney gave his first hand recollections of New Year’s Day 1937 when the gambling casino Monte Carlo wrecked on Coronado’s beach. As a Hotel Del Coronado lifeguard Dick was already on the beach that morning as the news of the wreck broke around town. He and his brother, along with many others gathered on the beach to see what they could salvage. Kenney reminisced, “People were running past us the other way carrying roulette wheels, lumber, furniture, booze, you name it. I saw a dealer’s table in the surf and ran out to retrieve it. I kicked open the drawer and found it filled with silver dollars, lots of them, the old Morgans’, which really

felt like a silver dollar.”

Dick Kenney wrote and sent poetry in lieu of Christmas cards. Four years ago he published his booklet, “Christmas Greetings.” (Eber & Wein Publishing, in Pennsylvania. The copyright is 2011 and the ISBN number is 968-1-60880-125-1.) Many of the poems he wrote while being held captive in Germany during WWII – where his thoughts turned daily to home, family, and the holidays. “Seeing this sensitive side of such a great warrior was always a pleasant experience,” said Joe Ditler, former director of CHA and a close friend to Colonel Kenney. The Colonel would always introduce Ditler as, “My publicist.”

After such a varied military career, Dick Kenney also published his memoirs under the title, “Sailor, Soldier, Airman.” (Also with Eber & Wein Publishing. The copyright is 2011 and the ISBN number is 978-1-60880-095-7.)

Poems:

Untitled

I am going home for Christmas

Though I am stationed far away

I can see the tree and the presents there

I can smell the pine and the turkey too

I am going home for Christmas

In a year or two

I can feel the warmth of the hearth

And see the glow of the twinkling lights

I am standing under the mistletoe

And waiting for a kiss

I am going home for Christmas

I’ll make it a good one, too

I can’t get home in person

But I can conjure up a vision

Of warmth and love and you

Merry Christmas

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Untitled (also)

Curmudgeon that’s what I am

I think Christmas is a scam

I know Xmas is a ruse

The only good thing is the booze

Next to me the Grinch is a piker

I am a whole lot tighter

Save the forest don’t cut a tree

Be a grump just like me

So why am I writing this Christmas card

And struggling to be a bard?

I caught the bug in spite of me

It’s the season, can’t you see?

Merry Christmas

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coronado residents will hopefully always remember Colonel Dick Kenney for his patriotism, bravery under fire, generosity and kindness. Colonel Kenney heard of the Coronado Historical Association’s (CHA) quest to purchase an original, 1923 Model T truck that had been part of the Hotel del Coronado’s fleet of laundry trucks in the Roaring Twenties. In 2007 he funded the purchase, at great expense ($14,000), and donated the vehicle to CHA saying, “It’s time she came back home to Coronado, where she belongs, and here is where she will stay.” It doesn’t fall on deaf ears to hear that comment now, and realize it also applied to a war-battered young man coming home from WWII so many years ago. That same day, Colonel Kenney, caught up in the spirit of Coronado history, donated five silver dollars he had recovered as a young boy from the shipwreck Monte Carlo in 1937. They are now on display at the Coronado Museum.

Dick loved his country and his hometown, Coronado, and was loyal and generous to both. He was forever grateful to and a supporter of The American Red Cross for keeping him alive when on the brink of starvation as a POW. “Without the Red Cross packages, many of us would not have made it,” he would say years later. “Towards the end, there wasn’t enough food for the guards so the prisoners got next to nothing,” he said. Colonel Richard Kenney is Coronado’s hometown hero.

Dick received his first Purple Heart from wounds received in action while flying out of North Africa, in June of 1943. Volunteer researcher Robert Sabel unearthed evidence that Colonel Richard Kenney, USAF (Ret), was due a second Purple Heart to go along with his many other medals earned in wartime service. Colonel Kenney was weakened by starvation and exhaustion, and yet he survived the march that so many others did not. In the process he received frostbite on his hands and feet. After reading Kenney’s story in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Sabel phoned Kenney saying, “I think you qualify for a second Purple Heart for injuries sustained in that march.” The Colonel would have nothing to do with it and snapped back, “I already have a Purple Heart.” Friends of Kenney however, pursued the project and, 68 years after the march, he proudly held that second Purple Heart in his hands a story that was covered by numerous newspapers and television stations.

Colonel Dick Kenney is survived by nephews, Dick and Bill Dean, his niece, Dorita Mickelsen of Coronado and several great nieces and nephews. The Colonel passed peacefully in his sleep the morning of December 11, at his Coronado home. He was 94, and had outlived them all. Colonel Richard Kenney was buried in the family plot at Fort Rosecrans.

Much thanks to Joseph Ditler, writer and of course close friend of Colonel Richard Kenney who submitted his name and wrote much of this information in previous articles about Colonel Kenney’s life. Thanks also to close friend Dot Harms, who assisted in the editing of this document, and was a bright light in Colonel Kenney’s life until the very end.

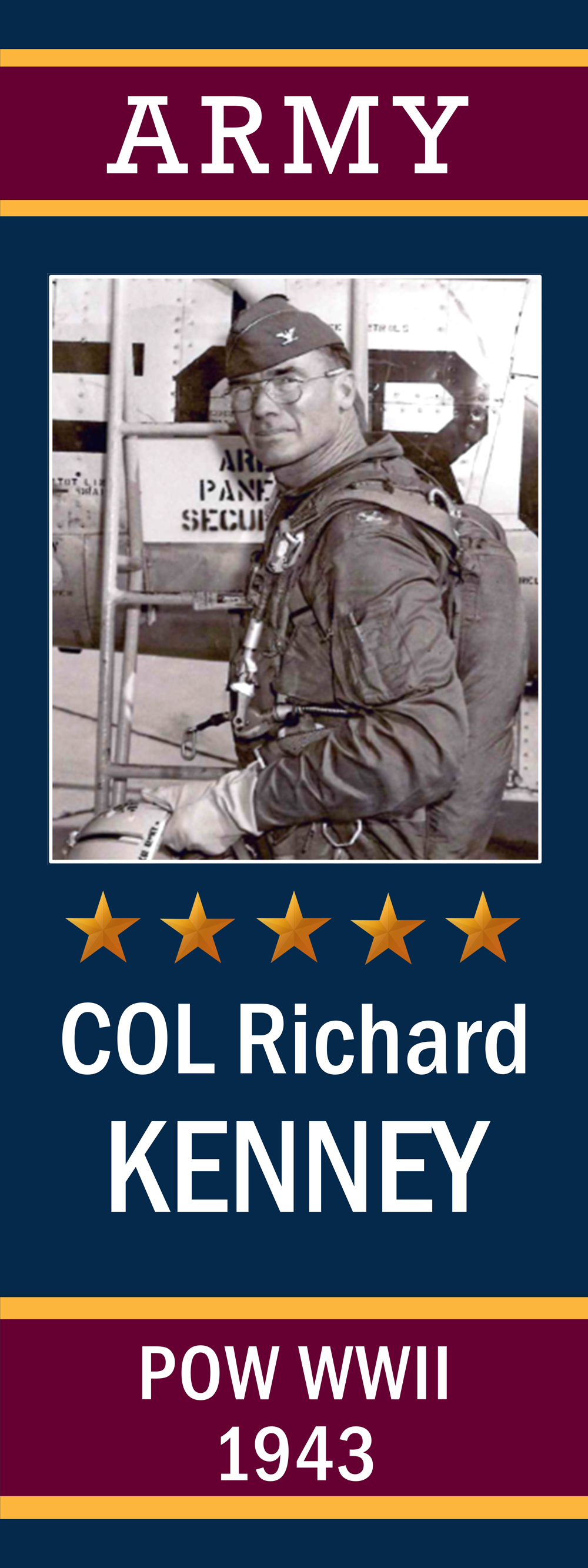

*Note, Kenney’s Avenue of Heroes Banner is displayed on Third Street and I Avenue, at the corner of the newly designated, Glenn Curtiss Park, in Coronado California, May 18, 2015.

Next week’s Avenue of Heroes biography will be Lieutenant Commander (LCDR) Richard Engel USN, Vietnam, By Coronado Scribe, Toni McGowan, May 2015(Banner at Third and J)

By Joseph Ditler, with contributions from Dot Harms and C.L. Sherman. May 11, 2015

Sources:

1. Coronado Eagle & Journal – (Challenge in the Sky Above North Africa)

http://www.coronadonewsca.com/news/coronado_island_news/another-side-of-memorial-day-coronado-man-recalls-duel-in/article_01a9ad9c-e699-11e3-a271-001a4bcf887a.html

2. Coronado Common Sense – (Second Purple Heart 68 Years Later)

http://coronadocommonsense.typepad.com/coronado_common_sense/2013/01/colonel-dick-kenney-prefers-no-fanfare-second-purple-heart-arrives-via-the-mail-68-years-later.html

3. eCoronado.com (obituary)

https://coronadotimes.com/profiles/blogs/coronado-s-colonel-richard-kenney-wwii-sailor-211220142114

4. This brief biography is based on the detailed work of Joe Ditler.